- Home

- Jocelyn Brown

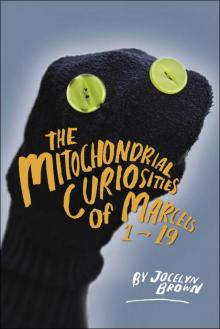

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Read online

THE MITOCHONDRIAL CURIOSITIES OF MARCELS 1 - 19

BY JOCELYN BROWN

copyright © Jocelyn Brown, 2009

first edition

This epub edition published in 2010. Electronic ISBN 978 1 77056 157 1.

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also acknowledges the support of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Brown, Jocelyn, 1957-

The mitochondrial curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 / / Jocelyn Brown.

ISBN 978-1-55245-209-7

I. Title.

PA8553.R68724 M48 2009 C813'.6 C2009-900821-1

for my sister Alison,

with love

One

We miss the bus.

We miss the bus because the car wouldn’t start, it took forever to find bus fare, forever to get up the hill, and the #5 trolley had to emerge from Middle Earth. Then we miss the transfer because in Edmonton you have to take at least two buses to get anywhere and things are timed so you always miss the transfer no matter how fast you run. So far, this bus-missing experience is no different than all the uncountable others. No one stops, and I look like crap.

We watch the bus get sucked onto the bridge, which is also the same as ever. All of Edmonton, in fact, is desolation as per usual, like the set of a low-budget apocalypse movie, so low-budget they used old white sheets for both the sky and the ground. We watch the cars, not for poignant insights but because what else do you do in Edmonton, Alberta, on a Sunday morning? You watch traffic. It’s the only sign of life.

It is 10:10 a.m. The memorial pancake brunch for my dad started at ten on the other side of the very long bridge. So much for parental death being momentous.

I lean against the bus shelter panting and queasy but also scanning for clues because I can’t help myself. Leonard dying means no gala treasure hunt for my birthday, which, talk about ridiculous, is also today. I was supposed to start my new life and instead it’s all about his being over. Not to sound melodramatic which I’m not.

I sink onto the bench where I will possibly stay forever and lean against Penny Shemkow, real estate agent with blacked-out teeth. An hour ago, I was pretty much convulsing, having had let’s say six cups of French roast in between changing the ear studs, the nose ring, the bangs, the top. When it’s your father’s memorial you think you should try your best, regardless. Now I look like hell on a stick anyway.

Joan, mother, and Paige, perfect sister, have more faith in the goodness of bus drivers. Plus, they’re generally better people than me so they run, actually are still running when I sit down to be embraced by sloth and Penny Shemkow. At the crosswalk onto the bridge, they yell my name until I open my eyes. I wave them on, they keep yelling. ‘Leave me alone,’ I yell back and point at my head, as in aneurysm. They discuss and I look at my hands, checking myself for some sign of life, but my hands are not that. They’re upturned like dead birds, probably killed by the hideousness of the skirt underneath them. So I look up at the trees because trees are a sign of life, the symbol of life, are they not? Dead. I look at dead branches splayed against a milky sky, completely sinister, because it’s all about pollution. And I think, as I do in moments of difficulty, about my blog, which features a weekly craft, as in, potentially, crafts for emotional release when you’ve missed the bus to your father’s memorial and the skirt you made for it totally sucks and you’ve just turned fifteen meaning there could be another fifty or so years to go, and because of the planetary situation, not to mention your own psychological issues and recent crimes, which can’t be considered just now, these fifty years will be more painful than even you can imagine. Something simple, I’m thinking. And soft. Maybe with fleece.

OMG. Paige is jumping up and down like a crazed cheerleader, shouting, ‘Dree Dree Dree.’ Joan walks towards me, doing a crackly low kind of Dreeeeee that sounds like Velcro ripping.

So, fine, off we go. Joan says, ‘These things never start on time,’ as if she goes to pancake memorial brunches for dead ex-husbands every Sunday morning. No point in saying it and the words wouldn’t come out that way anyway, so I just plow ahead.

There are three things about the High Level Bridge: it is high, haha, it is windy and it is très long. I look up and sleet shreds my face. Down below is the river into which at least one Edmontonian per year jumps, for obvious reasons. I keep my eyes and feet on the yellow line that runs down the middle of the walkway. When a bicycle bell rings, I don’t move over. My dad died, I think, deal with it.

The quadriplegia zone is so windy that Paige gets slammed against the fence. We cluster, Paige in the middle, bumping against each other until the zone of certain death. If this bridge is ever going to collapse, now would be an excellent time. ‘Well, I won’t have to go for my run tonight,’ Joan says at the light. At the door to George’s Grill, she says, ‘We should be done by three.’ When the apocalypse is underway, Joan will still be making a schedule. ‘No later than three, we’ll still have time for cake and a movie.’

‘Joan. Let. It. Go.’

‘Oh no, honey. It’s your birthday.’

‘Not anymore,’ I say. ‘Come on.’

‘What? But, Mom,’ Paige says. ‘Birthday cake today? What are you saying? Exactly?’ Paige, once the apocalypse is underway, will write a book on etiquette. How to behave during a plague. I am not kidding.

‘And what are you saying?’ I say, still holding the door open.

Joan’s taken off one of her shoes that she bought for this event although she pretended she had them before, and says, ‘What was I thinking, my feet are killing me. Girls! What are you waiting for?’

Paige tells Joan she looks great, but c’mon, Joan is never going to look as good as Rita who Leonard married two years ago. Anyway, Joan, good marks for effort.

Rita is right inside the room where the hostess normally stands. ‘Oh, thank God,’ she says. ‘I kept surrounding you in white light, but still – ’

Really, before this moment, Rita wasn’t a problem to me. In fact I was happy – okay, not exactly happy, but relieved – when she first surfaced. She was cool to be around, reasonably, given her wardrobe, and, most importantly, she came with a house. So, as soon as Leonard hooked up with her, I knew where Leonard was. And that was very good, because visiting Leonard post-Joan/pre-Rita was dangerous. Seriously. He lived in houses for which the words icky, creepy and disgusting are tragically inadequate. We’re talking mouse poo in the sugar and smells you do not want to identify.

Okay, here’s something truly unseemly: Rita and Joan both work in the addiction centre Leonard went to. Joan’s the admin person whose mission is getting someone fired every year, at least one person. I don’t know if she gets a raise for doing it or what, but that’s her mission. Strangely, she hasn’t gotten Rita fired. Rita’s a counsellor and that’s how she met Leonard. We don’t talk about that because I don’t think counsellors are supposed to do it with their clients. Rita also teaches yoga and I even went to one of her classes, which was my très generous attempt at bonding. Leonard was all pleased.

George’s Grill was Leonard’s one semi-healthy habit. We came here about a thousand Sunday mornings while Paige and Joan went to church. Maybe they still don’t know. Them: small dry communion hosts. Us: fat, buttered blueberry pancakes. Sorry, Jesus. So, you’d come in, you’d hear Willie Nelson, you’d say, ‘Thanks, George,’ after he said, ‘Don’t you look fabulous, Andrea,�

�� and you’d get your pancakes. It was the best possible way to start Sunday – stuffing yourself on high-fat carbs while reading the news with Leonard. That is the George’s I want to remember.

The George’s I walk into involves incense, drums, as in the embarrassing kind, and ten pounds of ashes previously known as my father. And that’s only the front. The back tables? A long row of moon faces staring at us with hungry little smiles. In the middle, four big tables full of AA people, mostly guys, mostly skinny and ponytailed, all swivelling their heads around like pigeons. I turn back to Rita. What have you done, I think.

She has this whole gauzy thing going on that begs to be set on fire. Bits of fabric and bangly bits hang everywhere. She holds out Leonard like he’s a box of cookies then pulls him back like no, she wants him all to herself. Joan’s still doing this apologetic thing about the bus. Rita looks confused, probably because she doesn’t get the concept of public transit, then says, ‘He loved you girls.’

‘He liked you too,’ I said.

OMFG. I bend down, extended eye contact with Rita not being what I need, and I say, ‘Hey guys,’ to the drummers. ‘Guys, can you stop that? It’s hurting me.’

When I stand up, Rita is testing the mike and says, ‘Leonard is in such a peaceful place.’

‘Unlike us,’ I whisper to Joan.

How incredibly strange that after walking through basically a tornado, Paige still has a perfect French braid. She goes straight to a table, very sensible, and, like Joan, disassociates. Before this, I have never looked at Joan and thought, OMG, poor you. I have thought other things – I mean, Joan inspires thoughts of a violent nature. But I’ve got to say I feel sorry for Joan as she squeezes between chairs to get to a table. I think, god, can you imagine being married to someone for fourteen years and reproducing twice with them and sitting at a table off to the side at their funeral thing? How wrong is that? I say, ‘Mom, we’re going to order some food.’ What else do you say? I want to make her something, crochet a bright and funny lizard. She likes lizards which, at the moment, is endearing.

The purple waitress is our server, always purple top and hair-band. She takes people’s orders in a whisper as if eating is the most embarrassing thing you could possibly do. And so she whispers, ‘Would you like to start with one?’ which is what, in fact, I usually do. Joan kind of nods, weakly, and Paige puts up one finger, and I hear myself say two blueberry and two buttermilk. I re fill Joan’s coffee like I always re filled Leonard’s and get more hot water for Paige’s peppermint tea. The photo’s been above the coffee machine since forever, but when I see it now, my heart hurts: Leonard, George and a couple of their friends smiling after a big breakfast. Hey, Dad.

Paige is the only family member who doesn’t pay serious homage to caffeine which is maybe why she can sit so still for so long. Maybe she’d like a lizard too – no, she’s more squirrel. Maybe that’s tonight’s blog: memorial crafts for surviving loved ones. My blog is for people who genuinely don’t have money, not the ones who happen to have tons of excellent supposedly free stuff lying around or a car to shop at the best Value Villages out of town, not to mention a glue gun, soldering iron and colour printer. That’s just to point out that waiting for your father to be memorialized is like every other kind of waiting as far as your thoughts are concerned. They don’t change.

Everything I can think about had been thought by then except the thing that can’t be thought – which is, WHERE IS IT, DAD? Where is it? And so while George, who loved Dad, clears his throat into the mike, I scan the room. It’s true, Dad, I’m looking to see if you left a clue in the restaurant although it’s totally illogical because you didn’t know you were going to die, but OMG, where can it be? You cannot have left me with nothing. You cannot have ditched my gala birthday treasure hunt. It’s like I’m on a different planet that looks exactly like the old one. I’m supposed to be in Toronto in two days, Dad, so c’mon. Get it together. But there you are, in a box smaller than my backpack. I did an excellent job on the collage.

‘Leonard passed on,’ George says, which is what kind of phrase? His voice shakes and he starts again. ‘Leonard passed on while walking around his lake with his beloved Rita, two of his favourite things.’ Ouch. Things? ‘He went in a place of beauty and he went in peace.’

Not exactly, George. Because first Leonard said, ‘Let’s sit down,’ then he said, ‘Oh no,’ then he crumpled face first into a pile of logs. Rita told me exact details. ‘I couldn’t turn him over,’ she said. ‘And you know your dad wasn’t that big. That’s how I knew he was gone, you know, dead weight.’ Nicely put, Rita. The last ten minutes have lasted basically a decade, so how long was Leonard’s last minute? Really long, I’m guessing. And how beautiful is face down in a woodpile if you’re not a chipmunk?

What you realize when you’re in room full of older people, I don’t know how old, but at least as old as Joan and Leonard and mostly older, what you realize is that they know life sucks. You look at their faces and they know they’re putting in time and, yes, they have their little rewards like TV and alcohol and pharmaceuticals and yoga. But nothing means anything, you can see it. I don’t know if it’s always been this way, you can’t imagine it has, because then what’s with reproduction? Revenge? Anyway. If I needed evidence that the whole human experiment was over, and, really, I don’t, but if I was about to have an optimism seizure, well, all I’d have to do is look around and, uh, no. What does everybody clearly know once they’ve tried out something supposedly major-life-event like marriage? Dread plus hunger minus ambition. Which is what I feel sitting there not seeing a clue to my fifteenth-birthday treasure hunt. I order another pancake.

A lot of AA people have to talk. I’m Bob, I’m Joe, I’m Francine. Really, when you get down to it, the whole funeral thing is a performance event for people who otherwise can’t get enough attention. How mean is that, but Bob just said, ‘Leonard saved my life,’ and I seriously doubt it because after Leonard’s first AA meeting, he emailed me to say, ‘Never become an alcoholic. You can’t imagine how boring these people are.’ Nobody talks about the things he loved, like his Coleman stove, or the things he hated, like Liberals. And nobody talks about how genius he was at treasure hunts which anyone who was really his friend knows. Only one person mentions Paige and me and not how much he loved us.

If you’ve ever sat on a suitcase with all your weight, that is pancake number six. A woman two tables away smiles at me as I cut it up. I smile back and Joan turns to see and goes all oh-hi, but doesn’t look exactly happy. ‘Who’s that?’ I whisper. ‘Old friend from Timbley,’ she says.

I conquer the pancake then crochet like a demon, especially when the drumming involves tambourines. At least they don’t know that Paige plays handbells. The lizard tail’s almost done, and I’m all about getting it pointy. We’re bubbled in our sadness, and it’s just about over. Rita invites everyone over to her home, still Leonard’s home too, she says, to chant and scatter his ashes. How heinous. But I have to go look through his den. Joan half-smiles at me, as in it’s almost done, when Rita says our names. ‘I’m so honoured to know Leonard’s girls,’ she says, holding up Dad. ‘Dree? Paige?’

Joan takes Paige’s hand and reaches for mine but when everyone looks at us, she shrinks into her chair. ‘It’s okay,’ I say and heave myself up. Rita’s holding Leonard up again. ‘Did everyone see Dree’s beautiful work on Leonard’s – ’

‘Box,’ I say. ‘It’s a box.’ I hear a hushed oooh, possibly internal because once I’m in front of Rita, I know what acid reflux + clamminess + room spinning equals. I totally would have made it, but Rita pulls on my arm. The dam breaks. Unspeakably gross. I actually hear a splash. Joan springs like a panther and propels me to the bathroom like mothers do. It is de finitely one of my top ten disgusting moments – in fact, next to when the hamster exploded, the most disgusting moment of my life – partly as a gastrointestinal event, partly as female bonding ritual. Every female in the building is now in this bathroo

m. Between rounds two and three I lock my door to keep them out of the cubicle.

‘Is she all right?’

‘We’re sure going to miss him.’

‘It’s her birthday – ’

‘Joan told me –’

‘Well, he tried – ’

‘Oh, honey, we’re so sorry,’ someone says to Paige.

‘She had too many pancakes,’ Paige says.

‘She looks so much like him.’

I try to say, Could you leave please? It comes out like Kwoodlepees.

The door swings yet again and clickety click, the sound of Rita shoes. ‘Joan, what can I do, I feel terrible.’

‘Nothing, Rita. There is nothing you can do.’ Joan’s voice is flatter than my hair.

‘George can give you a ride to the house.’

‘We won’t be going to the house, Rita.’

‘I will,’ I try to shout. It’s like someone cut the power. Silence.

‘Dree, this is awkward?’ Paige whispers through the crack of the door.

Joan’s right there too. ‘Honey, your –’

‘Do not say birthday,’ I say.

*

Okay, so, hopefully, I’ll have no memory of the memorial, but you’d think it would feel significant to have your father’s ashes on your lap while sitting in the chair you helped him choose at Sears. But no. Life is totally banal and, surprise, so is death.

Upstairs at Rita’s house, weirdly alone because Joan and Paige refused to come, I go through everything, including the computer. My backpack’s full of his magazines and office supplies, mostly paper clips which he loved and so had multiple boxes of and also his favourite pens, the Bic R3 Fineline. I have his overdue library books and a bunch of little things and I don’t want anything uncontained so, yes, the little plaid suitcase comes with me too. It has lived on the bottom shelf of his bookcase forever, home to the most hideous art on the planet. He’d put up the clown painting every few months or the creepy sketch of death and always Joan would say, ‘For god’s sake, Leonard, take that damn thing off the wall.’ I get the worst jolt of all when I unsnap the case because now I’ll never know why he liked these pictures and also, there’s the box of teeny white envelopes he used for treasure hunt clues. Blank. I check the side pockets. I check them again. And again. I rifle through the envelopes. He was all excited when he found them at a garage sale. ‘Will you look at these, girls? We’re in business.’ Not anymore, Dad. I take the pictures out despite deep empathy for their ugliness and leave them on the shelf for Rita.

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19