- Home

- Jocelyn Brown

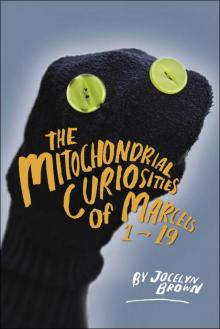

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Page 4

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Read online

Page 4

‘Dad. Dad,’ I say, ‘you’re dead.’ It’s worse than telling him, ‘No, I’m not going to Crescent Falls with you and Rita because I’d rather work at Booster Juice.’ That time, he said, ‘Well, it’s your choice.’ Now he drops the bag and says, ‘Oh Dree, Dree, I am so sorry.’ His voice is low and shaky. ‘It’s okay, Dad. I mean, it’s not your fault, but the special account, Dad, the special account – ’

Bam. My head bounces from window to windowsill to seat. Someone’s pulling my toes, dislocating them, actually. I hold my head as the dream evaporates. ‘Wake up,’ says Paige. ‘You were talking.’ I still cannot speak. ‘I could hear you all the way to my seat,’ she whispers, shoving my legs over and squeezing into the aisle seat. ‘People were looking.’

‘My head,’ I moan.

‘I didn’t mean to. You were practically shouting, “Over here, Leonard, over here.” How embarrassing.’

I press my hand over the key, still there under my sweater.

‘What’s wrong? What?’

‘I was communing with our dead father.’

‘I fail to believe he would talk only to you, even if he did like you better, anyway.’

‘He did not.’ I hold my head. ‘Is my forehead swelling?’

‘No. Well, excuse me for caring.’

‘Really, I think you ruptured something.’

‘As if.’

‘My sixth chakra could be leaking.’

‘Stop it. What did he say?’

‘Nothing.’

‘I knew it.’ With that, Paige does one of her military pivots and goes back to her seat. I press both hands against my forehead in case chi is spurting out. Lame, but if chi is real I can’t afford to lose any more of it.

Oh, oh yeah. I just got Step Five, ‘The Divine Offering.’ So obvious. A chakra device for Jojo Bunting. I’ll use the red wool conveniently in my bag although possibly the red wool has been fatally infected by rejection. Can a Divine Offering still be divine if it’s made from tainted material? I sit up and reconnect with nyrrrrrrrr. Listen up, Dad. I need to make a critically important life-altering decision.

Clearly, I would never have knitted Telinda Roberts a scarf out of said red wool, except Telinda was part of Santini’s let’s- find-Dree-a-peer-group mission because Telinda lusted after Zow, head anarchist. Really. And I thought anarchists liked red and would be thankful for a little floral embellishment. But no. At Telinda’s b-day party to which everyone knew I was pity-invited, Telinda got forty-dollar organic hemp Che Guevera T-shirts and picked up my scarf like she was holding a dead rodent by the tail. I called you, Dad, to say, ‘I’m dying, pick me up.’ And you didn’t come and I was irreparably damaged. You never knew how grisly, truly grisly, my adolescence has been. From then on, I was such a total outcast that even Santini gave up on peers.

Ha ha. Cast out by a knitting project.

Exactly. And then, Dad, just before I ran screaming to the bus stop which was six blocks away and meant waiting twenty minutes and transferring twice, Amanda Sills tucked her perfect hair behind her perfect little ears and whispered, ‘God,’ to Gabby. ‘God, what’s she doing here?’

Our future politicians. That’s what Leonard always said after heinous peer-group tales.

Whatever, Dad. Should I use the red wool or not?

Nothing.

Forget it. Red is not the right colour for divine anyway. It should be indigo. Leonard, what if I go to the hospital you used to work in? Can you figure out how to talk to me from there?

Nothing.

The bus stops in front of Liquidation World which is clearly enough said, and we step into the magical land of Timbley, Alberta. Paige yanks on my sleeve as we get off the bus. The train station used to be here and the grain elevator was down the street. I’m not exactly Ms. 4-h. I’ve never even touched a cow. But the grain elevator? That’s when the world started to end. The Timbley grain elevator crumpled, and a week later, so did our family unit. We were in the crowd, Leonard and I. Two tractor things clawed at the grain elevator, this guy beside me kept taking off his glasses and wiping his face, and everything was quiet except for kathunk, kathunk. Finally the whole thing folded in on itself, all slow-motion, dust covering everybody. I coughed like crazy and Leonard said, ‘Dreebee, I’ll be back in a few minutes.’ He went into the hotel, meaning at least four hours. I walked to Grandma’s, and we watched Murder, She Wrote, Paige on the floor getting her hair brushed by Joan, me and Grandma winding wool. The back door opened but Leonard didn’t come into the living room and we didn’t say anything to him or each other. That was the last time Grandma and Leonard were in the same house.

Thinking about Leonard is like painting a picture in reverse. I take something away every time I remember him – another place he’ll never be, another thing he’ll never say. If I could see the hole where the grain elevator used to be, there must be blanks in the air or the energetic web or whatever the hell Jojo Bunting calls it where Leonard was once.

Paige pulls on my sleeve, again, still mad but not crazed. Some guy in the parking lot is talking to her from his truck – the kind of jacked-up, big black truck that should say how insecure am I on the licence plate. Driver guy yells something repulsive and totally cliché and I give him a behind-the-back finger as we walk away.

‘Paige, I’m in trouble,’ I say. Her eyes widen and she gasps dramatically. Oh. She thinks I’m pregnant. For a second, I let her, if only because, wow, she thinks it’s possible. She rolls up her sleeves, a good sign, and ignores truck-driver moron who pulls a U-ie to yell more obscenities and further establish his manhood. That helps us focus, except then there’s intense honking and I have to look. ‘OMG, humans are so over,’ I say.

‘I am not participating in your nihilism.’ Paige picks up her pace.

‘I am not a nihilist – look at these people, the whole traffic thing, can’t you see it?’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘We’re going down.’ She marches off and I exert myself to keep up. ‘Paige, that wasn’t it.’

‘I hope Grandma reduced her dietary fat.’

‘Seriously, my issue is worse.’

‘Correction? She has diabetes and problems with her thyroid.’

We walk silently for a block, past Eve’s Dentures and the bank, and hey, Jerry’s Fish & Tackle Shop is gone, and in its place? A miracle. Even Paige is impressed by the sign. ‘Haha,’ she says. A row of four fluffy sheep smile at us. In small letters underneath, the sign says 4Ewe Wool Shoppe. The sheep encourage me. Also, the shop maybe means that anything’s possible, so I take a big breath and go for it. I make small adjustments, as in Dad had two special accounts, one for you, one for me, and I borrowed ‘a bit’ from Joan’s credit card. Paige nods through the whole thing. Maybe she is a saint.

‘So, Paige …’

‘Please, God, don’t let her ask for my money.’ Paige holds the cross around her neck and looks up.

I hold the key. ‘Jesus would want you to help family first.’

‘I fail to believe you even know what mitochondria are,’ she says.

‘Powerhouses, Paige. Mitochondria are to cells what you are to me.’

‘You are so screwed,’ she says.

The Sockra

According to my research, being spiritually successful, as in rich, is all about having open chakras. These are invisible energy centres, and they can get blocked or they can leak. When that happens with the head chakras, as in the top two (highly spiritual, so more money), what you want is grounding. And what can be more grounded than rocks and socks?

1. Take two socks and overlap toe sections.

2. Take one round flat spiritual-looking rock. Paint a fish or spiral et cetera on it.

3. Sew overlapped toes together, leaving opening for rock to fit inside.

4. Insert rock.

5. Lie down and put Sockra on forehead so rock is between eyebrows and socks cover eyes.

6. Become rich.

Five

G

randma Giles’ apartment smells like burnt sugar and cat, which anywhere else would be disgusting. There, it’s Divine Bliss. Which means how evolved am I, since Jojo needed Tibet for her db. Anyway, capital-A Abundance. Receptors opened and multiplying.

One of the million fabulous things about Grandma Giles is the way she greets us. ‘Ohhhh,’ she says before the door’s closed. ‘Ohhhhh, my girls.’ It’s the lowest sound possible, the kind of sound for when the world ends and we’re all trapped under rubble taking our last breaths. Ohhhhhh, we’ll all say to each other, as in, Goodbye fellow humans, our species is finished. Louis the cat slaps his tail against our ankles and hopes we’ll put something on the floor for him to pee on.

‘Actually, Grandma,’ Paige says, as Grandma Giles grips her, ‘actually, one full-spectrum bulb is all you need in the living room.’ As usual, the apartment is blindingly bright.

‘Ohhhh,’ Grandma Giles says. ‘Anyway, I don’t drive.’ She wears the magnetic apron I made her, her metal measuring spoons stuck in a perfect row along the waistband into which I skillfully sewed magnetic tape. Paige says ouch as Grandma Giles pulls her in tighter. Then Paige holds the ends of her braids, her latest obsessive-compulsive response to stress. Minor epiphany. Talk about convenient. Paige pulls hair; I think abundance. A piggyback compulsion. Braid/abundance. Perfect.

‘My poor little birthday girl, so exhausted.’ Grandma Giles holds my face and looks deeply into my eyes. ‘I have made fudge.’ Paige sighs in her dietician-to-be way and touches a braid. Abundance.

‘Excellent, Grandma,’ I say. Excellent. Grandma Giles’ hair smells like cigarettes, citrus shampoo and Clairol Nice’n Easy Almond Bliss. I breathe deeply.

‘Grandma, I can’t believe you still have that clay lamp,’ Paige says. Braid. Abundance. Grandma is already in the kitchen, and Paige blocks the hallway. ‘I mean, it’s such a blob.’

‘It’s called Trinity,’ I said. ‘That lampshade rules.’

‘It looks like a UFO.’

‘Exactly.’ My lampshade phase was brief but prolific. I made them after trying to make a lamp, which involved electrocution, which involved bodily fluids, hair loss and so much pain I listened to CBC without changing the channel for an entire day.

‘Have you ever considered sex with aliens, Paige?’

‘I fail to believe you find that funny.’

Abundance.

Look at her, $1,200 sitting in the bank doing nothing, but, no, she can’t stand my crafts in this living room. ‘How about with random strangers? Seriously, Paige, if God gave us hormones – ’

‘Stop.’ Paige holds a braid like it’s a rosary. ‘Number one, as if you’re Ms. Experience. Number two, that frame. It’s like I’m buried under garbage.’

Paige is fixated on the photo frames I made for this year’s mug shots. ‘Collages of found objects, as in art, Paige.’

‘Correction, Dree. Debris. Please tell me you disinfected.’

Interesting. School-photo Paige is surrounded by a teeming mass of pathogens. Replicating themselves like crazy as we stand there. I pick up one of Grandma’s old photos. ‘So, something more classic? Like this?’

‘I am not giving you my money for orphans in Africa.’

‘Jesus would,’ I say. And then Jesus jerks my hand and all the photos crammed onto the TV fall against each other.

Braid. Abundance. Braid.

‘Ohhh,’ GG says, back with a platter of fudge. ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry, get away from there.’

‘Just one that’s broken.’

‘I said, leave them.’ As Grandma grabbed the photo out of my hand, I looked at it, because Grandma never grabs anything. ‘I’ll find a new frame tomorrow,’ I say, but she ignores my outstretched hand. ‘Have some fudge.’ Or else, says the silence that follows. Paige and I stuff big hunks in our mouths and Grandma wraps the broken frame in a tea towel and puts it on her lap. Louis digs his claws into my thigh, his way of saying, Pet me, things are effing tense in here.

‘Actually, Grandma.’ Paige pauses which is not what Paige ever does after actually. ‘Actually, Joan recycles our art projects every six months. So, you don’t have to keep my crafts, it’s just little – ’ Kill me. Paige pulls a recipe box out of her backpack. Stencilled. OMG, with what? Penises? Grandma Giles squints like crazy at the row of tiny phallic whatevers. ‘Actually, Grandma, mushrooms and zucchini have complementary nutrients.’ I slide the photo off Grandma’s lap and under the sofa while she considers the abomination in her hands.

‘Look, Dree, they’re so perfectly spaced.’

‘Wondrous, Grandma. How did she do it.’ Penis penis penis. It’s all I see, which means? Anyway, so what. Why not ornamental genitalia? If sex is so natural, so thousand-thoughts-a-day, why isn’t there wrapping paper, T-shirts and water bottles decorated with happy little vulva et cetera? How come it’s all about cleavage which, hello, is probably about breastfeeding, as in, Where’s my mommy?

‘Well, it’s just beautiful, Paige. I’ll put it right here beside your sister’s lamp.’ I can tell Grandma Giles truly thinks it is beautiful because she’s sad which is Grandma Giles’ version of happy. She loves beautiful things and they make her sad. If the world were fair, Grandma Giles would have enough money to sit and look at sunsets and flowers and feel sad. She clutches the heinous recipe box and stares at the fudge. Fudge used to make her happy as in sad but she can’t eat it anymore with the whole diabetic thing. I take another piece on her behalf.

Maybe it’s Grandma’s sadness, maybe the stencilling, the anti-craft, or maybe it’s my overstuffed manic head. I have to sleep. My body wants to slide right off me and become a puddle. It slides into the chair instead. ‘Pass your sister that blanket,’ says Grandma. ‘My poor little Dree. Worn right out.’

‘And that Rita woman,’ she says to Paige. ‘Your poor mother.’

‘You should have seen what she was wearing at the brunch, Grandma,’ Paige says. Paige is Grandma Giles’ reporter, as in, voice of Joan re: things Grandma can’t ask Joan directly about.

‘Ohhh, poor Joanie. What a service.’

‘Correction. Pancake brunch, Grandma.’

And so on, including the waitress with the low-cut crushed velvet top and big red belt. My mouth can’t move, otherwise I would have defended the belt.

‘Well, maybe it was best I couldn’t come.’

‘Exactly,’ says Paige.

Pause. Meow from Louis. As in, Okay, Grandma, here’s where you can’t avoid saying something.

‘Ohhhh, poor girls. I’m so sorry.’

Bloody hell. She can’t even say his name. Grandma Giles hated Leonard.

‘Someone from Timbley was there.’

‘Who?’ Grandma’s voice jumps.

‘Rose someone. I thought she was a guy at first,’ Paige says. ‘Then Dree threw up so I didn’t have time to talk to her.’

Cow.

I wait for Grandma to answer but hear trees instead, huge shaky evergreens on the hospital grounds. Leonard stands in their shadows waving me over and I stand on the second-floor balcony of the old hospital. There’s no railing and a long long drop. I lose sight of him and wake up to my own shrieking. Actually, no. It’s Grandma’s smoke alarm which means supper’s almost ready. That’s literally the drill every visit because, except for me, Grandma’s smoke alarm is the most sensitive thing on the planet, and it goes off whenever something boils on the stove and every supper she boils potatoes.

Even with the killer beeping, the only part of me reasonably awake is my bottom lip because it’s busily hatching a cold sore. It used to be that Grandma’s was the magic bad-food bubble. I could eat a pound of fudge plus Cheez Whiz plus buttered everything while watching six hours of TV and wake up feeling great. Now I’m one big virus, or maybe my bottom lip is a microcosm of my life or even Edmonton life if possibly the number of viral molecules equals Edmontonians.

‘I dreamt about Dad,’ I say at the table before filling my mouth with mashed potatoes, ultra

-creamy because Grandma Giles uses insane amounts of butter.

Grandma hmmms and tells Paige butter is nothing to be afraid of.

‘Correction, Grandma.’

‘My mother put butter in everything, you know.’ Grandma passed me the butter dish, knowing I was her ally in all things high-fat. Strangely, she did not say, as she usually does, ‘Ohhhh, the last piece of Wedgewood, and once I had so much.’ Nor did she list the entire Wedgewood family, the crystal, the silverware or the linens that had kept the butter dish company, all of them wedding presents, all of then trashed when her house burned down. It was a long list and usually took us right through to dessert. Tonight, though, she says nothing, and Paige and I take turns saying, ‘Yum, Grandma, yum. This is great.’ Maybe she’ll tell us the fire story later because, otherwise, the visit will be very weird. She has to tell it over and over like turning compost. When Joan was about five, Grandpa Giles fell asleep on his La-Z-Boy with a cigarette, probably drunk. They lost everything including his job since he was a fireman. From Timbley high society, which is really not too high on the food chain, they went to basically paramecia. ‘“Ben and that poor Rowena,” that’s what they called us,’ Grandma would say.

I open my mouth and hope for the best. ‘So, in the early nineties, you and Joan and Leonard all worked together at the old hospital, right, Grandma, at the old hospital?’ Spontaneity does not work for me. Grandma Giles smooths her hair back and holds her head as if it might blow off. I have too many competing emotions to notice dread.

‘Well, I think it’s time to celebrate our little birthday girl.’

Paige gives me a mechanical pencil wrapped in recycled something while Grandma furiously makes sundae supremes. Slam slam slam. Cupboard doors and jars onto counter.

Oh god. The walnuts.

Grandma has this thing about keeping nuts and raisins way too long and this other thing about not wearing her glasses. These things are not compatible. And I don’t move fast enough.

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19