- Home

- Jocelyn Brown

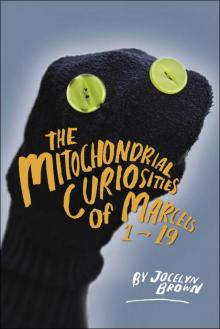

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Page 10

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Read online

Page 10

The Timbley Times is on low buzz. People come and go, sloshing coffee into their mugs without ever standing still. I go straight to the archive shelves because why complicate things by asking. Rose is at the back, yelling about some photo that’s disappeared, and everybody’s ass in on the line until it’s found.

Okay. 1994. I have to read the headlines again, have to know how bad it was. Otherwise, Dad, I don’t get how you could be such an effing jerk.

I haven’t found the page yet when Rose bangs through the swinging doors followed by High-Waisted Pants Guy. ‘Heya, Dree, I didn’t expect – ’ Rose says. ‘Wait for me in my office, Donald.’

‘Remember when you said I could stay over, you know, help Jessie with her Social project?’

‘It’s so good to see you,’ she says, all auntie voice. Ahhh. Warm regard. As good as apple crisp. ‘Dree, she needs some time. Listen, give me a few minutes – you okay with this?’ She points to the 1994 book, I nod, and she whips round to ask Donald did he have a stroke this morning, he needs to explain Page 3 otherwise.

I fixate on the first headline, the day after Christmas, ’94, and then skip a few days ahead to where Leonard is first named. The story is squeezed between ads for Shur-Grain Chick Starter and Craxton’s Radio and Television Service. God. If one of my future traumas ever gets reported, please god, not between chickens and TVS. Okay, Leonard, I can almost like you again. Well, I can be something other than completely appalled. I catch an article I missed first time through. Staff too afraid to come forward, claims union. According to unofficial reports, staff are being threatened by hospital administration regarding the Letorneau suicide. Dr. Rinkel, chief medical officer, says the claims are nonsense. So, there really are people feeling guilty out there.

‘The processor is down,’ someone yells while re filling her coffee.

‘Christ,’ Rose yells back, pushing aside a cubicle divider to walk into the room. ‘And it’s magically fixing itself while you stand here, Shirley?’

‘I’m going, I’m going,’ Shirley says.

‘You know,’ Rose says to me, looking at the article, ‘you know, I always wanted to print something saying your dad got shafted. But no one would talk.’ I keep my eyes on the yellowed newspaper. ‘Listen. Jessie thinks you’re great. Just give her a bit more –’

We both cringe at the sound of whatever Shirley’s done to the processor. Rose goes, I get on my coat. Great? Not loathsome and utterly repulsive? Jessie thinks I’m great?

‘Hiii,’ I yell after tripping over the step into 4Ewe and dropping the suitcase. Hiii, as if I had been dropping by every day this time for about six years. ‘Sorry,’ I say when I see her on the ladder. ‘Sorry.’

She looks down and keeps stuffing wool into a wall shelf. ‘Hey.’ Voice dry as old bologna.

‘Did you get my emails? There were only a couple, well whatever, a few, never mind, it doesn’t matter.’ My face goes red, the rest of me curdles. Tragic uncoolness. ‘I brought you something.’ She flinches when I unsnap the suitcase and then recovers in the same second.

‘I’m kind of busy.’

‘I’m pretty sure your dad made it, my dad had it – ’

She’s beside me holding the picture all in one move, and I explain it was always on the wall, took me a while to remember it looked kind of like your drawing, and look, TL at the bottom.

‘I see it. Your old man had my father’s art?’

‘My dad was maybe his friend.’

‘He let my father kill himself then took his art?’ Jessie doesn’t take her eyes off the picture as she edges away from me.

‘Maybe they were friends, maybe your dad gave – ’

‘My dad gave his life.’

‘So my dad got blamed for everything and – ’

‘Well poor effing him. Do you mind?’

‘What?’ It comes out like waaaa.

‘Look, it’s not about you. My number one? Avenge my father’s death.’

‘Avenge?’

‘What?’ She squares off, hand on hips.

‘Well, avenge. I mean, what a word.’

‘It means to get revenge.’

‘I know what it means. Just – it’s so Batman.’ The suitcase is still open which means Marcels, Marcel ingredients and Paige’s half-done purse fall out. ‘Sorry.’ Silent hostility is never good for me, even when I’m not crouched on the floor of a wool shop, so I keep talking. I tell her I discovered something amazing about Christmas and sex, she’d love it, and also, would she like Marcel 19, the last one, with gloves and green boots. After she shakes her head without even looking down, I trip on the step on the way out and make it back to the Times office without looking up.

I have to talk to Rose. She can make Jessie like me again, maybe. I don’t hear any talking from outside her cubicle, so I slip in between the portable room dividers. But Rose is there, standing, and so’s Donald the computer guy. The cubicle is small, and Rose and Donald aren’t, and suddenly there we all are, too surprised and too close to speak. I lean back out of the way, forgetting that it’s not a real wall, and so I just keep going, the divider thumping Shirley who slams against the archive shelf. The sounds of destruction are loud and various and end with the coffee pot smashing against the concrete floor. Well, technically, the last sounds are Donald saying, ‘Man down, man down,’ and Shirley saying, ‘Sweet Jesus.’ A long silence follows with everyone standing over Shirley and me, me pulling my top down to cover my gut.

My mind refuses to participate in the moment. Really, square root of blank – until Rose puts her hand on my arm and says, way too kindly, ‘Are you okay?’

I’m a terribly crier. We’re talking serious mucous involvement plus red blotches plus sweating. Rose asks Shirley if anything’s broken and why the hell she’s still lying there then. Shirley says it’s the only goddamn way she can get a break. Donald and the others get operational and Rose pulls me into her de-cubified room. She takes an energy bar out of the desk drawer. ‘Have some protein. No, really, you look like hell.’ I take a bite because it’s the easiest thing to do. Then I produce a lot more mucous.

Thirteen

Except for all the dead people, and me, nobody’s here. Talk about quiet, especially in the ancient section. The gravestones are all crumbly and tilted, like they’ve been chatting and eating crackers. Rose said she comes here to talk to Tim, so maybe Jessie does too. He’s probably way down by the benches where everything’s shiny and straight. That’s where Grandpa Giles is, next to Anton Starchak whose big black headstone says ‘A noble example was his life.’ Poor Grandpa, a fireman whose house burned down while he was passed out drunk on the couch, and he’s stuck beside someone perfect for eternity. It’s bad enough sitting beside Paige for ninety minutes three times a week.

I’m post-adrenalin relaxed and feel like drifting around here smelling pine and imagining the grief of others. As in the parents of ‘Our darling Annie, 9 months & 13 days,’ who has a mossy lamb on her stone. ‘Weep not, Father and Mother, for me, for I am waiting in glory for thee.’ Oh, right. Très comforting.

In the new section, a lot of the headstones are flat, like labels on a massive underground cabinet, so it’s crowded and I probably won’t find Tim. I don’t really know why I want to anyway.

Maybe I’ve finally summoned Leonard because is that cigarette smoke? I lean against the willow, the last thing between me and the smoker.

‘Go, on,’ says the woman, holding out a Tupperware container. ‘Tastes like a holiday.’ She’s eating grapes and smoking. Versatile. I take a couple and say thanks.

‘Did you know Tim Letorneau?’ I rock on my feet like a weirdo but momentum feels important in a graveyard.

‘Nope.’

‘How about Leonard Johnson?’

‘Nope.’ She points at a gravestone. ‘You ever hear of Roger Blackstone?’ No. ‘Got him that carnation.’

‘Wow, that’s real?’ I say, because we are talking screaming red.

‘Roger w

ouldn’t go for nothing fake.’ She puts a lid on the grapes. ‘Bunch of Letorneaus over there, six rows down, maybe ten.’

I thank her, even though she has turned away, and walk by dozens more dead people. I wonder if I’ve ever walked by someone or sat beside someone on the bus who died that very day. At least one, I bet. And I’ll never know who. Someday I’ll be that person to a bunch of other people.

Did Leonard feel relieved, even a little bit, as he died? No more AA meetings, no more car problems. All done. All the work of being human, done. Maybe that’s what Tim needed, what they all got. Okay, Dad, really, do you resent not having a tombstone? Because I’d have visited wearing long black drapey things.

Robert Letorneau. Marie Letorneau. Sylvie, James, Donald. At the end: Timothy Michael Letorneau. ‘Hi,’ I say. ‘Please make Jessie like me again. And if there’s something I’m supposed to do, let me know.’ I pull out Marcel 19 and explain Marcel’s mitochondrial curiosities re: transformative power as I wedge him into the base of the gravestone. The trees rustle back.

Cushion of Good and Evil

On one side of this cushion cover, your face is framed by happy colours and flattering trims. On the other side, the same photo is transferred onto stained fabric and slashed, ugly, possibly painful items are glommed all around it.

You need:

A photo of yourself, at least 8 by 12 cm Photo-transfer paper, or some other way of getting photo onto fabric. Happy trim and ugly trim Thread and/or glue

1. For the good side, cut a square of nice fabric slightly bigger than cushion to be covered.

2. For the evil side, cut hideous fabric 5 cm longer on one side than nice square. Transfer the photo onto each side.

3. Decorate each side.

4. Slash ugly side (to make opening for cushion).

5. Stitch sides together all way round.

6. Insert cushion through slash, then safety-pin together.

Fourteen

There they are, evil hospital and bland hospital, like a bully and his nerd. I take a circuitous route to Door 12 of the new hospital, my exit from the last craft-room visit. I’m all stealth, also hunger, two frozen grapes being tragic as breakfast when you’re marching up massive hills in a friendless state of acute anxiety.

Blinded by the light. This is how that saying got invented, by walking into a hospital and hoping an evil doctor isn’t standing at the other end of the hallway. I rub my shoes on industrial carpet, blink furiously and imagine the encouraging oinks of the display-case pine-cone pigs as I head for the craft room.

‘Well, Dree!’ says Louise, queen of crafts.

I want to tell her everything. I want to fall on my knees and beg to stay forever, to be the craft nun or something. But it’s packed and Louise is trying to cover five people plus Mrs. Brandt and Bernie the wallet guy. So I stay quiet and breathe in the divine craftness of it all.

‘Are you okay, dear?’ Louise says.

‘Totally,’ I say and take the only empty chair, next to an origamizing woman. I ask if she’d like some help. She looks at me all gratitude and joy, and I smooth out.

‘Rowena Giles and her fancy piano fingers,’ says Mrs. Brandt.

‘Oh, give it a break,’ says Bernie.

‘So why’s this called the Tim Letorneau Centre?’ I ask. May as well jump right in.

‘Real artist, that guy.’ Bernie looks at me.

‘You knew him?’

‘Painted a whole wall. How d’ya think he got the paint, that’s what we want to know.’

‘An entire wall? Where?’

Louise rolls a cart to the table. ‘Bernie, let’s get you – ’

‘Did the whole thing one night, next day – ’ Bernie sticks out his tongue, holds his neck.

‘You were there?’

‘Dree, could you help Sandra please?’ Louise gives me the look. The shut-the-hell-up look I know so well.

As soon as I get up, Mrs. Brandt starts the Fancy Rowena thing which probably I shouldn’t ask about either. Sandra is two people down from her, so once I sit back down, out of sight, out of mind.

Really, crafts are the best way to process information. You get a steady weaving, sewing, whatever thing going and the brain clicks along. Leonard worked a double shift that night. Leonard got Tim that paint. These thoughts bounce around with a few others as Sandra and I roll Fimo snakes. When the thoughts settle into facts, it’s time to go. Please, craft gods, let me return to this temple. Seriously, I am praying. The origami lady gives me a paper crane which causes emotion, so I say a global ‘Bye, take care,’ and move on out.

‘Oh! Dree!’ Louise calls. I do an over-the-shoulder wave, my face being too hot and prickly for full frontal.

And I’ve gone out the wrong door, the main one, which means main hallway. I merge with a post-lunch group, imagine snatching lunch bags from skinny people most likely to have leftovers, and hear the second-worst thing possible.

‘Ohhhh!’

‘Grandma!’

‘That is you,’ says Grandma Giles. ‘What on earth … ’ She waves her friend Brenda away, and repeats, ‘What on earth?’

‘Well, the craft room, Louise says maybe I can get a job sometime.’

Grandma Giles cocks her head and says, ‘What?’

‘Just thought, you know, I’d check it out. But wow, what’s up with Mrs. Brandt?’ I keep babbling, can’t stop, need more words to cushion that question and the next. ‘What does she mean by fancy fancy Rowena Giles in 54E ?’

‘Ohhhh.’ Grandma doesn’t notice the kitchen people saying hello as they wheel a metal cart by. She looks past them, scanning the hallway.

‘Rinkel,’ I whisper. ‘You’re afraid of Rinkel, right?’

‘You shouldn’t be here,’ she says but motions me to follow her to her office. ‘You don’t want to know about all that, have something to eat, poor little Dree.’ Grandma roots through her desk then her purse, and hands me packets of crackers crumbled enough to call sand. ‘People should leave the past alone.’

‘Grandma, c’mon.’ She looks at me all sadness and shock and yes, I am a terrible person. Nothing new there. Her phone beeps, she doesn’t answer, and we hear the receptionist say, ‘Yes, Mrs. Giles is here today, did you try voicemail?’

‘Okay, Grandma, I’ll go right away, but how about a timeline?’

‘So long ago.’

‘Basically, we’ve got three things: 1) Thirty years ago, your house burned down, which creepy Mrs. Brandt knows about; 2) Twenty years ago you land this job, which evil Dr. Rinkel supervises; 3) Fifteen years ago Tim Letorneau kills himself and my dad gets blamed. 1, 2, 3. They’re all connected, and why won’t you tell me how?’

The photocopier kicks in, giving us noise cover and maybe a better pace.

‘I had no choice,’ Grandma snaps. She stares at the filing cabinet and talks in a low whisper, kind of like Rita doing an omi gomi chant. But Grandma’s on the wrong story. ‘One minute you have a beautiful house, everyone envies you, then one cigarette … Joanie ran to the Brandt house, smart little girl, but that crazy cow didn’t tell anyone Joan was there. Can you imagine? I thought she was inside the house.’

Oh. I stop fiddling with paper clips. ‘Mom was missing?’

‘For hours. That’s what froze me up. I couldn’t move or speak for days. Grandpa was beside himself.’

‘So he brought you here.’

‘Nobody knows except Brenda,’ Grandma whispers.

‘We’re talking thirty years ago, as in my life times two?’

‘Patients are patients, staff are staff. He was very kind to hire me.’

‘Rinkel?’

‘Dr. Rinkel.’

‘Oh, don’t tell me.’

Her phone beeps again and she stands up. ‘Ohhh, so much work to do.’

‘Okay, sorry.’ I stand in the doorway, put my scarf on and whisper, all urgency and regret. ‘So Rinkel was your doctor thirty years ago and for the last twenty he’s been your boss which means what r

e: Dad, I’m sorry, but what?’

‘Please, Dree.’ Grandma holds up a stack of papers. Repeat: I am a terrible person. Nonetheless, there’s one last unstoppable question.

‘Were you working the day Tim died?’

‘Ohhh.’ Grandma adjusts one of the fish magnets on her file cabinet, one of a set I made her last year. ‘I came in Christmas Day to cover for the little reception girl, she had a new baby, and when I smelled smoke, ohhh – ’

‘You pulled the alarm.’

‘Dr. Rinkel was on the men’s ward and I ran up. Don’t worry, I was going to tell him, only smoke.’

‘I heard Dr. Rinkel tell Leonard to leave Tim,’ Grandma says softly. Oh, god. I lean against the wall. My legs don’t have bones anymore. I have no words.

And you never told anyone, I think, OMG, not even Joan?

‘Why did Leonard listen?’ Grandma continued. ‘Would you leave your friend alone? Would you make friends with a patient in the first place? Would you?’ Grandma’s voice is all about accusation, not asking, and she doesn’t look at me. ‘Where else could I work? The pizza place? The bowling alley?’

She glances at me, measures my reaction, and I say ‘Grandma?’ That’s all. I don’t know what I mean: maybe Grandma, is this really you? or Grandma, is this really reality? or Grandma, are you okay? She nods to who knows what.

‘Hello, Dr. Rinkel,’ the receptionist says, and before I can move, there he is. ‘Rowena. I’ve been calling.’ A voice like stomach cramps.

‘Ohhh, Doctor. My granddaughter, Dree.’

‘We’ve met,’ he says, trying to stare me down, clearly not knowing that staredowns are the primo survival skill of today’s youth.

‘This is no joke, young lady. Trespassing – ’

‘Manslaughter,’ I say. Grinning. Legs shaking.

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19