- Home

- Jocelyn Brown

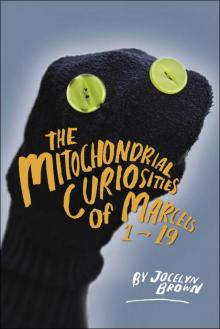

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Page 9

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Read online

Page 9

Violent and abusive is not what I had hoped for in terms of personality type, and in the first hour in emergency I stare at the wall while Paige bleeds onto my favourite belt and I think, Violent and abusive. That’s me. You don’t think you can ever be like that, then bam. Literally. Alcoholism must be next.

For ninety minutes, I sit there hating myself the way you’re supposed to when you break your sister’s face. The Marcel bag is on the floor beside me, but I hate myself too much for crafts. ‘Sorry,’ I say again.

‘Oh, girls,’ says Joan, on her tenth disease brochure, this one about breast cancer.

Paige covers her nose with both hands.

There are eleven people scattered in the waiting room, and except for the really really old person, we are all watching paramedics push a stretcher through, oxygen mask and lots of nurse action, but I can’t see the patient. That’s how Leonard came through, I bet, maybe with Emergency full and a crowd watching.

‘Well, that’s quite the out fit,’ Joan says and the group stare clicks in again. A woman totters on stilettos, sparkly white four-inchers, and carries a guitar. She takes off her coat, arranges her complicated blue out fit, gets the guitar out and settles into a bench to strum away. When the nurse comes over, the woman says, ‘Oh hello, I’m Lakshmi,’ and gives her a paper. Then she sings ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ all soft and breathy, followed by ‘This Land is Your Land’ and something in French. Most people turn back to their magazines halfway through ‘Puff,’ but OMG. It’s after midnight by now and so weirdly excellent that I’m describing the whole thing to Leonard in my head. We’re closest to her and she smiles at me every few lines. After her third song, she comes right over to us. ‘Oh no,’ Joan says.

‘It’s my offering,’ she says. ‘Music lifts everyone’s hearts.’ She comes whenever her throat tingles, she says. She wasn’t going to come tonight, but tingle tingle, so she had to.

W.O.W. ‘And the hospital’s okay with that?’ I ask.

‘I have a letter,’ she says with a big smile. ‘When you’re heart is open, others have to follow.’ Joan goes to the bathroom, and Paige is essentially fetal and possibly asleep. Lakshmi’s eyes fix on my bag of Marcel supplies and she pulls out Marcel 7’s torso. ‘So, you’re gifted, too.’

‘Correction,’ says Paige. ‘She broke my nose.’

I am about to put my hand on Paige’s back and say sorry again, but Lakshmi is between us and she gasps, ‘Poor you!’ She pats my hand. ‘You must feel terrible. When I was sixteen, I pushed my sister down the stairs and broke her arm. I’m still healing.’ Paige swears for possibly the first time in her life. Lakshmi goes off to sing ‘Puff’ again and I turn to covertly sew Marcel 8’s head into a point. Maybe Paige really is sleeping now. Joan comes back and dozes. A security guard talks to Lakshmi and she leaves, waving and smiling at me, and I hold up the beginning of Marcel 9. Eight of the eleven people have gone in, four new people have arrived, then another stretcher, then Paige’s name is called and I wake her up.

‘Yup, it’s broken,’ the doctor says, ‘nice and clean. No brain damage probably.’ We laugh because we are too tired not to, and because that’s what you do at three in the morning when your emergency doctor makes a joke. Laughing is laughing, though, and while the doctor talks about ice for Paige’s swelling, Paige hates me a little less. I take off my coat and work on Marcel 10’s eyes.

Dr. Belinsky explains what Paige’s face will do over the next two weeks. ‘Yup, black and blue then blue then yellow. That’s when you go to your doc, get it checked.’ Paige keeps saying oh no. Joan goes to leave a voicemail for Alex the boss about coming in late that day. Marcel’s eyes and Paige’s nose are done at the same time, and the doctor looks at Marcel sitting in my palm then snatches him and says, ‘She’s wonderful!’

‘Marcella,’ I say.

‘Marcella!’ shouts the doctor, a little too happily. ‘Marcella! I’ll be right back.’

‘Time to switch to decaf,’ I say. Paige doesn’t smile and I apologize for the millionth time. ‘I am so so sorry, Paige. Does it still hurt?’

‘No, not at all, it’s great,’ Paige says. Sarcasm will never be her thing. She sits while I discreetly commit a small crime re: new craft supplies. From the hall, the doctor exclaims ‘Marcella!’ again and we grimace. That much energy this late hurts. Paige pats her cheeks again and winces. ‘Too bad you and Dad can’t have a great big laugh at this.’

‘Paige, never –’

‘As if. I heard you.’

‘No way.’

‘Sainty Paige.’

‘He never said that.’

‘So, where’s my special account?’

‘With mine.’

‘As if. Dree’s so creative, Dree’s so – ’

‘Paige, I’ll get a job, I’ll pay you back, I promise.’

Out in the hall, someone shrieks with maybe laughter. ‘Belinsky, what is that?’

‘That, darling, is going to get us through the night,’ says Paige’s doctor.

‘Another gastro in D,’ says someone else.

‘Exactly, my beloveds. Her name’s Marcella.’

The doctor pops back holding out a ten-dollar bill. ‘It’s all I’ve got and we need her.’

‘Just keep her,’ I say. ‘No, really.’

‘Aren’t you just a dolly,’ she says. ‘But here.’ She puts the ten bucks on my lap and turns to Paige. ‘And you, my beauty. The schnozz: ice it, don’t pick it, see your own doc in two weeks. You’re still gorgeous.’

Joan comes back and asks again about Paige’s breathing. We’re done. The doctor leaves, Paige puts out her hand for the ten, and we walk by the counter where Marcel 8 is squished between a pencil holder and the wall. He looks happy.

For the first time since forever, my path is clear. Joan drops onto her bed without taking off her shoes and Paige says oh no over and over in front of the bathroom mirror. I wash the blood off the wall. I wait for Paige to go to bed then book a Greyhound ticket to Timbley for the day after tomorrow which makes me queasy, being really wrong. My heart’s guidance cannot be argued with even if my heart is basically trampled into hamburger. I’ll go to Jojo Bunting and I’ll see Rita and I’ll get the Tim picture and I’ll bring it to Jessie and Jessie will understand everything. It’s so obvious.

I take the seven remaining Marcels and head downtown. It’s still dark which means the possibility of being murdered especially at the top of the hill. But maybe it’s been a long night for psychopaths too. Things feel universally sleepy.

After a couple of hours, I’m coming back down the hill with one leftover because I remember the man on the bus and the Dante statue. The other six are perched in phone booths downtown.

Cake Decoration Device

Desperation makes people do questionable things and mine made me take five ear thingies and a latex glove out of an emergency room. Of course, if the doctor actually checks your ears, you don’t have to commit a sin to get one. My ears were not checked but I did have to medicate my stress levels somehow. Anyway, I hereby vow to use this cake decoration device in service to humanity.

The excellent thing about the ear things is they come in different sizes for kids and adult ears so you can squirt different thicknesses of icing at the same time. You don’t have to use all five fingers. It depends on your personal ratio re: control/fun.

Materials:

1 latex glove

1–5 ear thingies

1. Make a tiny hole in finger tip/s, and stretch glove over big cup to stabilize.

2. Pour boiling water into glove to wash away latex nastiness.

3. Leave to dry for a few minutes, then put ear thing inside finger and poke tip through.

4. Fill glove with icing or any other substance with decorative possibilities.

Eleven

I lie back down on my blue mat in conference room C of the Convention Centre and rearrange my sockra so I’m in actual and not just spiritual darkness. I’m surrounded by 500 other

losers including Mr. Santini. At least he’s a few bodies away. At least I didn’t see Rita. The lululemoned woman beside me hums along with Jojo. So far it’s been twenty minutes of humming to open our chakras.

Once this is over, Cycle of Life Bowl Number 2. Obviously. Chapters 1 through 5 of Heavenly Riches are already shredded into teeny pieces.

Because how does Jojo Bunting’s book end? She talks all about her three mansions, her violin collection et cetera because God did not want her to share even if someone sent her a sockra which probably she’ll make billions from. She’s so deathforce. Obviously poor people choose poverty. Joan loves not having a working car or a life and I love killing orphans in Rwanda.

Someone starts on a drum, a slow steady pounding. I imagine telling Jessie the whole thing and smile. She’d die laughing.

Breathe into your heart centre, says Jojo, and whatever. Inhale, 2, 3, 4, hold and expand expand. Lots of breathing. Breathing into our toes and our calves and our knees et cetera. Ewww. As if anyone should ever breathe into their pelvis at the same time as their school counsellor breathes into his. Maybe I disassociate, maybe I concentrate harder. Maybe a lot of time goes by, maybe a second.

My jaw seizes, clamps down like a steel trap. Who knows what steel traps actually are, but de finitely they hurt like hell, because oh god.

I can’t breathe. My jaw squeezes tighter and there’s no air. My throat closes. There’s no air.

Darkness zooms out into haze, then I see the hooded faces again. They float far above me, don’t want to scare me this time, don’t show their empty eye sockets.

‘Get me out,’ someone yells.

They sway their hoodie selves back and forth to the drum, all aren’t we fun and rhythmic. They make a space in the middle for me.

‘Get me out.’

‘Okay, okay, deep breath in.’ A flash like someone took a picture.

‘That’s it, we’ve got you.’ Santini. Santini’s talking to me. He shoos someone away.

‘You had a release,’ he said, ‘perfectly normal.’ Jojo Bunting’s still humming. Everybody’s still lying down. The tornado in my head spins away.

‘Can you lend me five dollars?’ I ask Santini. He sighs. ‘So I can take the bus to Rita’s and back. I had this vision.’

I think I know what the Hoodies are trying to tell me. Rita has my money. Maybe she didn’t come to the Jojo thing because she didn’t have to. Maybe she found a lot of money recently.

I wait for the #56 outside the bus shelter because the guy inside it coughs disgustingly while talking on his cell and apart from the pathogens I don’t want to imagine how desperate the person he’s talking to must be. I’m standing in frozen slush, feet planted far apart, all tough-guy.

Fine, Rita, we can do this ourselves or we can wait for the cops. No, too lapd. Hi, Rita, I came for my money and I don’t have time to dick around. Right. If you can’t keep a straight face imagining what you’d say, don’t say it. Another rule to live by.

She doesn’t open the door. But you can feel when someone’s home and she is. I go round to the back, call her name and lean on the doorbell one more time.

I’ve never seen Rita without makeup, but no amount of cosmetics could help whatever’s happened. I say, ‘Sorry, I forgot to call.’

Her mouth is crusty and her hair is matted on one side and bulgy on the other, like a squirrel might be nesting underneath. A couple of Shreddies are stuck to the lapel of her housecoat, which is tied shut with one of Leonard’s joke ties, the Mickey Mouse one.

She turns the deadbolt as soon as I’m inside. I smell alcohol.

‘So, wow.’ I follow her into the living room. She ducks down low as she goes by the window and rasps, ‘They’re watching.’

‘They?’ Oh-oh.

She crumples into Leonard’s chair. ‘Youshuddabowlme.’

‘I should go?’

Rita raises a hand as if the right word can be plucked from just above her head. ‘Should. Have. Tolllllld me.’ The arm falls across her chest.

Oh. Oh god. She must have found it. I pull the piano stool right beside her and angle my head to get eye contact. ‘He probably didn’t think you needed a special account.’ I try for a decent pause. ‘Where was it?’

Rita glazes over.

‘Ssspeshlwhatspesl?’

‘Well, you know, account, or whatever, what did you find, is it in an envelope?’

I see a stack of bank papers on the coffee table. Underneath it, I see several miniature Absolut vodka bottles.

‘Yeah, go look.’ Rita’s arm flaps dangerously. ‘Go look at Lennie’s spechlecounting.’

I jump at the doorbell, which is followed closely by the door-knocker. ‘No!’ Rita hisses when I get up. ‘Goddamn sponsor.’ Rita waves me over to the papers and I kneel down at the coffee table, let Rita stagger up the stairs on her own. After twenty minutes, I still don’t get it. All I see are credit card bills, four different cards, all in Rita’s name, each bill at $5,000. My name’s nowhere. Neither is Leonard’s.

I follow Rita upstairs. Twice more the doorbell rings. From the bedroom window, I see a woman standing on the sidewalk looking up, red with cold. Rita lies face down over clothes and rumpled sheets. ‘Tell her Rita’s sober, Rita’s fine.’

‘But, Rita, I don’t understand Leonard’s account.’

‘No?’

‘He said there was a special account for me – ’

‘Maybe that bill hasn’t come yet.’

‘No, he was depositing money in – ’

Rita laughs or coughs, who knows which, and talks and cries in a long but mostly incomprehensible torrent. Eventually, I decipher. For the first time in my life, I have failed to imagine how bad things could be.

I run to his den, needing Good Leonard, Dad Leonard, kind, funny and true Leonard. The Leonard who doesn’t embezzle from his wife and lie to his daughter. The den is trashed. Books ripped, computer smashed – full-out demolition. I fall against the door and make a noise.

‘Time to go, speshhl grll.’ Rita wobbles in the hall. ‘Door’s this way.’

Oh my god. ‘Rita, I need to get a picture.’

‘You want something?’

The doorbell rings again. Talk about lucky. ‘Make them go,’ she says.

I’m diving through books, yelling about the picture, creepy, small, did she see it, and she wants to know why but not as much as she wants the doorbell to stop ringing. I see ghastly yellow and, yes, there’s the clown painting trapped underneath the tipped-over bookcase. I kick books aside, turn the case on its side, ignore Rita’s breath which is rank and in my face.

‘Make. Them. Go,’ she shouts. ‘Thiziz all mine, mine.’ For someone who can hardly stand, she’s got a powerful arm swing and I lose my balance when it connects with my shoulder. Talk about a fortunate fall. There’s the picture. It’s hidden under files and she doesn’t see me take it. She does see the key hanging from my neck when I stand up.

She makes an unspeakable sound. Ahhhhh is more or less what I say. She lunges for my neck with both hands and falls onto the books.

The doorbell rings again. This is one plucky sponsor. I run for the door yelling, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry.’

He didn’t know he was going to die, I keep telling myself on the bus home. He thought he’d be able to pay Rita back the forged credit cards, thought she’d never have to know. It was some kind of delusion because he was mentally ill, he didn’t mean to hurt anyone. That’s the best I can do and, frankly, Leonard, it sucks. My hand is around the key, ready to pull it off my neck, fling it away dramatically.

Twelve

Friday morning, I’m on my way to Timbley. The bus driver says good morning like he means it and I sit right behind him and imagine confessing. As in, Ohhh bus driver, have I ever messed up. In my head, he nods knowingly, says, Yup, yup, well, you had to make some tough choices there but good for you. You followed your heart. I replay the scene about fifty times and feel microscopically less loathsome. I

feel zero interest in finishing Paige’s wretched purse but pull it out of Dad’s little plaid suitcase anyway. At least I can get the damn strap done.

Maybe Leonard is also feeling confessional. He and Tim are doing the hey, yeah, hey guy thing.

Man, I really messed up with Dree.

You sure did, buddy, says Tim.

Also Rita, but Dreebee – she’s most important.

You betcha, says Tim. Smart girl you got there.

BTW, sorry about your suicide.

Hey, not your fault. Sorry I checked out.

Thanks, Tim.

The river’s solid ice, trees are stiff and bare, and the people on Calgary Trail walk like all their bodily fluids have congealed. It’s the kind of day you have to be driven through. All the sins in the world have solidified.

Somewhere, somebody’s felt guilty for twenty-five years because they heard Rinkel order Leonard outside that night, because they know it wasn’t Leonard’s fault Tim died. Maybe right this minute that person is feeling guilty, maybe he’s dying, machines beeping beside the hospital bed. His hand motions me to come closer because he, maybe she, is too weak to speak properly. I’ll tape the conversation, I need a recorder, then I’ll get a lawyer, sue Rinkel, surprise Joan with a new house. Joan will say, Can you believe this place, so fabulous and all thanks to Dree.

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19