- Home

- Jocelyn Brown

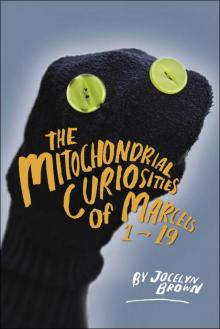

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Page 8

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19 Read online

Page 8

‘Go check your medication.’

‘Supper, how many times – Girls, supper.’ Joan yells as if we’re across a large field.

Her hands shake when she thunks the pot of Lentil Surprise onto the table. ‘Mmm, delicious,’ says Paige. Nice try. ‘Pass the plastic butter, ‘ I say.

‘Soy is an unsaturated fat, so much healthier than butter.’ Paige holds the plastic tub like she’s a priest doing the communion thing. ‘This is what Dad should’ve had.’

‘Stop.’ She does.

Supper will be lentil-related for the rest of the week because not only did the washing machine break and cost a fortune, but gas went up again, and they wouldn’t believe the heating bill. Joan looks up from her soup, eyes buggy, forehead bunched up like corduroy.

‘Really, Mom, this is great, Mom,’ I say. ‘Delicious.’

‘Yummy,’ Paige says.

We tell her Grandma sent down fudge for her and Paige will cook odd days and me evens. We say no, the house isn’t that cold, and no the lentils don’t taste that weird. Joan remembers the relaxation CD Alex gave her and yes, we think that’s a great idea, perfect, exactly what she needs. As soon as Joan slides her chair back, Paige rushes the computer. ‘Hey, how about I do the dishes,’ I say. That is the most gracious offer ever made and they totally miss it.

Every few minutes, Paige says, ‘What did you do to the computer,’ I say, ‘Nothing,’ and Joan says, ‘Girls, please.’ I finish the dishes, get out my Marcel supplies, and stay in the kitchen. When the seagulls and wave-crashing start to fade out, I assess Joan’s mental state. She’s still lying on the living room floor.

‘Mom, she killed the computer,’ Paige says.

‘God, you’re paranoid.’

‘Girls, please.’ Joan is wearing her target sweatshirt, possibly the most appalling clothing item on the planet. Alex the boss gave it to her. As in, Since you make way less money than me but work way harder, here’s a hideous sweatshirt made by other oppressed people. Happy Secretary’s Day. ‘He meant well,’ Joan had said. I look at the lurid orange bull’s eye. No, Mom, he did not, I think.

Possibly the primordial sound of waves does something to my brain. I have this embarrassing impulse to nestle my head against Joan’s shoulder and smell her v05 hairspray.

‘Marcel 3 will save you.’

‘Hmm,’ says Joan. ‘Very cute, but his hat’s crooked.’

‘So, whatever happened to old Mrs. Brandt?’

‘Whaaaat?’

‘You know, old – ’

‘My head’s killing me, Dree.’

‘I’m really sorry but was Grandma Giles ever a psych patient?’ Joan suddenly has way too many tendons in her neck. She keeps her eyes shut.

‘We’re supposed to do a family genetics thing,’ I say in a lame voice that makes Joan say, ‘Oh, really?’

‘Okay, sorry, ten seconds. Why did Grandma hate Leonard so much, was it because Leonard knew she used to be a patient and what’s with creepy Dr. Rinkel? What?’

‘You’re judging me.’

‘What?’

‘It may not be the most fashionable thing in the world, but he meant well – ’

‘No, it’s great, totally on target – ’

‘Totally cute,’ Paige says. ‘Mom, make her fix this.’

‘It’s not like people give me gifts every day of the week. You take what you can get.’

‘Joan, Mom. Really, I’m way too self-centred to think about your sweatshirt.’

‘Totally, Mom,’ Paige says. ‘Also, she destroyed the computer.’

‘It would explain a few things.’

We wait for pronoun clarification.

‘It would explain a lot. Like mother, like daughter.’ Joan stares at the ceiling and mumbles. ‘Mom loved Leonard at first, said he was a sweetheart.’

‘What about Grandma?’ yells Paige. ‘Tell me, tell me.’ She hammerlocks me and shouts in my ear. ‘What do you know?’

‘Let go of my neck.’ She doesn’t, so I say, ‘Grandma kind of lost it after the big fire. Right, Mom?’

‘When I was small, she’d stay in bed all weekend. And right now I could go to bed forever.’ Suddenly Joan sits up in one motion like she’s rising from the dead. ‘No other jobs, maxed-out Visa. I hate them. They’re not going to know what hit them when I’m finished, every time sheet, every memo, every single bloody – ’

‘Joan, I’m making you ginger tea,’ I say. It’s time to yell questions from the kitchen. I bang around the kettle, think about what I most need to know and read our collective emotional state. Swampland. I may as well get Grandma’s photo out. One way or the other, we’re going down. I clatter cups, yell tea questions, then, ‘So, did Grandma hate Leonard because of the whole Tim thing?’

‘Tim who? What? What, Mom?’ Paige is torn between comforting Joan and assaulting me. Joan talks too softly for me to hear, and when I bring the tea, Paige is kneeling beside Joan, stroking her hair. She swats at me. ‘Why can’t you leave her alone, that was ancient history.’

‘See, I need to get a new frame.’ I sit on the floor and show Joan the picture as if we’ve been talking about it for the last half-hour. ‘Did Grandma hate Leonard here?’

Joan closes her eyes but looks okay. ‘Rinkel got moved from treatment to administration after Tim’s suicide. He’s been Mom’s supervisor ever since.’

‘So, hey, why didn’t we even know about Tim?’ I cup my hand around Joan’s toes and use my softest, hey-no-big-deal voice.

‘Go to bed,’ says Joan.

‘Correction? Mom, it’s 8:30?’ says Paige.

‘Your dad was fired. Fired.’ That’s all Joan can say.

Paige and I don’t look at each other, which is possibly what all siblings do when they realize their remaining parent just cracked.

*

The house is so sad I sleep. I sleep deep and dark until the dark separates, like two-ply Kleenex being pulled apart. A layer of shadow ripples then another layer, this one cracked into squares, no, faces, a sheet of faces staring at me from the ceiling. They replicate like crazy, each new layer closer to my face. ‘Die.’ A voice sharp as a new X-Acto blade. ‘You’re going to die.’ Closer and closer they come, a million pairs of white circles where their eyes should be, flat faces shivering. Oh god, I’m cold. My quilt is nothing, a T-shirt in a blizzard. ‘Die, you’re going to die for this.’ One voice burning with hate. My eyes won’t close. I can’t get my breath. I am breathing them, I know them, I’ve always known them. ‘You’re going to die.’ Yes, yes I am and oh god, it hurts. They crush my heart, press down from the outside, strangle it from the inside, because the only breath I have is them. Their faces merge with mine and my eyes are empty sockets. Everything’s black. A thump. Pain everywhere. Thump. ‘I hate you hate you hate you.’ Oh god, that smell. That horrible smell.

Lentil Surprise.

‘I hate you.’

‘Paige, get off me.’

‘You stole my money.’

‘Borrowed.’

‘You stole money from orphans.’

‘Borrowed.’

‘In Rwanda.’

‘Borrowed!’

‘I hate you.’

‘I know. Get off me.’

Ten

If there are really sixty words for snow among the Inuit, why aren’t there at least twenty words for tired? As in, god-when-will-this-end tired, why-is-life-so-hard-yet-so-meaningless tired and there’s-nothing-to-wear-nothing-for-lunch-and-where’s-my-bus-pass tired. Then there’s wide asleepness when you’re so tired your head keeps drooping, so alert that everything is too loud, bright and sharply de fined. Oh. And then there’s extreme sleep deprivation because your sister beat you up in the middle of the night. That’s about ten types, and as I try to shield myself from Paige beside me and Ms. Riddell in front of me, I am all of them.

Riddell smacks a yardstick against the blackboard. The entire class jumps. ‘So, are we slaves to our genes, or do they work for us?�

�� Riddell says. ‘Can Dree choose to finish her mitochondria project? Or is she genetically programmed to ignore biology assignments?’

The entire class swivels around, as in, whatever, except I turn bright red. Paige closes her eyes and says, ‘Oh my god,’ as per usual.

‘The colour of your eyes, the curliness of your hair, your penchant for black, maybe it’s all encoded in your DNA. Another hundredth of a second and you would have been an entirely different person.’ Riddell smiles at me. ‘Be glad you’re you.’

‘Oh, exactly,’ I say. A titter undulates through the class.

I try to look slightly quizzical but mostly blank. Same look I gave Trenchey when he said what did I think I was pulling with the Death of a Salesman bowl, literature was no joke. Same look I gave Santini when he asked did I work things out with Rita/Mrs. Johnson, did I plan to go to the Jojo Bunting seminar, group energy can be a powerful thing.

Exponential tiredness means a weird but comfy underworld fog. Real life is softer and out of focus. The wall between live people and spirits feels thinner than usual, or maybe jiggled out of position a little, like the cheap room dividers at the Timbley Times. It’s a friendly fog, as if Dad and his spirit buds are a buffer zone between me and living humans. Look, Dree, they’re saying, all these people with hopeful lives? With all their achievements and goals? We’re going to be between you and them sort of like foam rubber, so it won’t hurt as much when they bounce against you. Actually, even the walk to school this morning across sad and futile Churchill Square wasn’t as lethal as usual. A guy picked up cigarette butts under the Epcor sign, and someone in brown ran by with a bulging laptop case. I saw my future – scrounging or working or both then death. But fine, nothing new. Of course when everything’s fine, you know you’re done. But I was too tired to consider that.

Riddell is passionate about cell death. ‘Dree and Paige, you are listening smartly, I presume, as you will be enlightening us further on the subject?’

‘We’re on it,’ I say. ‘Apoptosis.’

‘Mercy. Could you say that word again for the class?’

‘Apoptosis.’ Wow. Wherever that came from, thank you. I smile at Paige.

Except for bumping into everything, this would be the state of mind to stay in for life. Random flashes of intelligence. Strangely unbothered by everything. Immune to sibling hatred.

Paige is maybe a molecule less killer than this morning at the bus stop but hatred still shoots from her eyes. This morning she stood inside the bus shelter, encased in navy, and I stood just outside the door waiting for a car to drive through the puddle and cover me in freezing slush. I figured it would have been painful plus baptismal, and Paige was all about both.

I apologized again.

She squeezed her biology textbook to her chest so tightly I expected paramecia to fall out. She had many many words for how evil I am and how this affects the planet, as if I am personally responsible for global warming and every civil war in Africa. What do you want, I’d ask after every couple of sentences. So, what do you want? No response until, finally, she said her last pathologically selfish. Then she ripped a page from her coiled scribbler, handed it to me, pushed me aside and got on the bus. As per usual, she sat in front to talk to old people and I sat three seats behind. We both knew she wasn’t telling Joan anything since Joan was already boiling over. Still, I was in no position to negotiate.

1. Make Paige new shirt, Vogue pattern #1293, out of blue fabric with yellow checks no later than this Friday.

2. Make Paige three items on demand according to her specifications within three days of each request.

3. Give Paige a) crocheted belt (brown); b) beaded bracelet (blue and yellow).

4. Surrender all craft supplies not needed to make 1 or 2 to Paige as collateral until 1–3 are complete.

5. Paige has total access to Dree clothing and accessories until 1–3 complete.

6. Mitochondria presentation gets no less than A.

7. Failure to meet any of the above will result in full disclosure of theft to authorities.

‘This is totally unchristian,’ I say when we got off the bus.

‘Correction,’ she says, pointing her finger like Moses and quoting something biblical and damning.

Basically she owns me.

Riddell talks to us in the last few minutes of class. ‘So, apoptosis. Well, well, Ms, Dree. What are you planning for next week’s presentation?’ She’s hoping I’ve got more than one word. It does have four syllables. I smile the weak smile of the damned and wait for time to pass. It doesn’t, so I say, ‘I want to dramatize the turning point of our evolution. To show how mitochondria invented sex.’ The room pops with oh gods, yeahs and the raucous laughter of adolescents trying to sound experienced. ‘Excellent!’ says Ms. Riddell. ‘Excellent! Good work, you two.’

As it turns out, that was the best day of the week. By Friday I have accumulated many lifetimes’ worth of fear and resentment. Vogue 1293 has a sadistic collar and front yoke. No one’s said anything about Leonard except Bethany on our first day back, and all she said was, ‘Wow, that was so weird, how your father died just like that.’ How can death be such a non-deal when everyone’s afraid to die? Couldn’t the school or at least one of my classes wear black armbands even for a day? Shouldn’t every school have a big box of them for parental deaths? Today there’s a story in the paper Leonard would have loved. A woman in Texas pulled a gun on her hairdresser because he cut her bangs too short. Also, another ped got run over on Jasper Avenue. Dadness but no Dad. No one who says, ‘Dreebee, you’re a marvel.’ And it’s like nothing happened. I once made cookies for Jennifer when her budgie died FGS.

The week lurches by like one zombie after another, each one uglier and nastier than the last. The bags under Joan’s eyes get darker, Paige’s braids get tighter. I get more tired, which should be impossible.

A million times a day I check for Jessie messages but by Thursday it’s obvious. Not a single person on the planet likes me. I stand in the girls’ can looking in the mirror and see that my mouth has become exactly like Joan’s. Permanently downturned. There I stand being bitter about being alone but still being alone, probably for life because I’ve become bitter. Sophie and Erin come out of stalls, wash their hands and leave without saying hey. So now I’m repellent. From invisible to actively repulsive. Excellent. Like the guy in the bushes but I didn’t even have to grow a beard and blow my nose into it.

Friday is the one-month death anniversary. I can’t get out of bed. I can only think in big foggy letters and it takes the whole morning for them to spell out Leonard, where are you. I have to see him, can’t see him, have to get up, can’t. The Marcels look anxious. There are seven now, the baby socks having escaped capture by Paige. They’re lined up on my dresser like a tiny, pudgy construction crew watching with button-eyed concern. What, I say. Do you want to go to school? Do you want to try belonging?

More snow, overcast sky. The world feels like a basement apartment with teeny windows and a low ceiling. Maybe I can get a job and move out, try to finish school at night or something. I stare at the ceiling, wonder about the stain in the corner and remember the nightmare of hooded faces and Jessie’s drawing. And as my eyes move away from the stain and follow a crack, I remember why those faces seemed familiar – Leonard’s creepy little picture had the same creepy face, and I’d been staring at it my entire life. I’m sure of it. The picture I left on his bookshelf was a sketch, not painted, with more face less hood, kind of horrorlite. I’ve got to get it. I could email Jessie now, tell her I have something of her father’s. No. I don’t know for sure. But if it is Tim’s and I do get it, maybe Jessie will like me again. I take Marcel 6 for good luck. There’s something especially plucky about him.

Taking the bus to Millwoods and back takes roughly the same amount of time as flying to Toronto. On the way there, I crochet half a panel of Paige’s shoulder bag – number one of penance two. Rita isn’t home. The guy next door is shovelling and w

atches me walk around to the back. ‘Hi,’ I say. ‘She’s not home,’ he says. He waits to see what I’ll do next. I lean on the doorbell and sit on the steps. I’ll wait him out.

He wins.

School hours are way over by the time I head back so I can’t use my school bus pass. ‘What do you think this is,’ says the bus driver, ‘a limo?’ He and the woman in the front seat exchange sardonic-all-knowing smiles and he points at the door. The #81 guy is better, doesn’t kick me off, but won’t give me a transfer either, so I have another mile to walk once I get downtown, at which point I would have been on the shuttle out of the Toronto airport.

The only thing that makes me want to live a long long time is the new convention centre because when I’m old no one will care about teaching me consequences when I blow it up. You’d think it would be bad enough to walk by a concrete wall instead of the river valley. But, no. In front of the concrete death-box, big plastic letters in primary colours spell DREAM. As in, Are you serious? Dream of what? The river I used to see? Last year, Leonard stuck a clue on the M. Forgive the spelling, marvellous Drea; the word’s been urdered perversely. He taped a Second Cup coupon at the side of the M with the next clue. I got a mochaccino the next day and complained it wasn’t hot enough so got another coupon for any drink, any size, which is so golden even I have managed to save it.

A couple of guys are smoking at the picnic table in the remand centre yard but none of the street guys are drinking at their bench like they usually are because damn it’s cold. I’m frozen and compressed as a fish stick when I get home but because I’m me, no one cares except in relation to the supper I was supposed to cook. ‘Sorry,’ I say. ‘Nice of you to drop by,’ says Joan. ‘She was worried sick,’ says Paige. ‘Sorry! If I had a cell I could have called.’

‘Mom, it’s 6:30,’ says Paige.

‘I’ll make spaghetti tomorrow,’ I say.

Things go way too fast. Paige says, ‘Mom, do you want me to stay?’ Joan says, ‘No honey, you go-go.’ She blows her nose and tells me that someone at work gave her two movie passes, but they didn’t know where I was so Paige asked her friend. Whereupon Paige says, ‘Dree couldn’t go anyway, she has sewing to do,’ and lifts a foot to take off a Leonard slipper, now stretched all to hell. Somewhere between me telling her the slippers are not, will never be, part of my regular wardrobe and are exempt from #5, and both of us telling Joan nothing is going on, nothing at all, and Paige telling me to take off my crocheted beaded belt, she’ll wear it until I make her one which will be #1c – somewhere in there, one of us pushes the other and the other pushes back. Don’t ask me how, but Paige hits the wall face first, which actually means nose first. Which means a crunchy pop. Softer than a balloon being pricked, louder than plastic beads being pulled apart. Avec blood. Lots of blood.

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19

Mitochondrial Curiosities of Marcels 1 to 19